In China, the year 1931 is remembered with terror, anger and grief. That was when Japan began invading China, and in order to annihilate the Communist troops, the Japanese had to crush the foundation upon which the Communists existed: the support of people. Hence, the civilian population was terrorised into passive submission: villages were burnt down, men were killed and women were raped. Obviously these were immensely hard times for the Chinese, but leaving aside the bloodshed, it is worth looking into other possible effects the invasion had on women. Is it possible to find something that the Japanese brought that was truly positive? Even though these impacts are not obvious and came at the extremely high price of people’s lives–the Chinese people could hardly acknowledge something positive in the massacre carried out by the Japanese–it is easier for an outsider to see the silver lining. For instance, the Japanese invasion shaped Chinese women’s attitudes and developed a sense of nationalism and pride, and evoked a sense of feminism. What is more, even the most uneducated Chinese women began to show interest in political affairs, which led to the emancipation of women, and they began to gain high positions over the years. While some might argue that this eventually would have come in time, it is still worth analysing the changes brought on or accelerated by the invasion.

Status of Chinese Women

Despite the physical and mental humiliation and terror, the Japanese invaders themselves did not have a direct impact on the status of Chinese women. Manchukuo was a puppet-state that Japan established in China and set an example for the rest of the country: Japan tried hard to have as much influence there as it possibly could. Since the two cultures were to some extent intertwined, the question arises: how different were they? In Manchukuo, “during the Japanese occupation, women’s relationships within families and with the state were also intensely scrutinized as colonial officials sought to meld conservative Japanese ideals with Chinese Confucianism” [1]. The Chinese, despite debating the role of women in society following the May Fourth movement, were still fairly Confucian and believed a woman was not much more than a commodity. The Japanese officials were relieved to find out that a woman’s status was similar in both countries and did not have much significance in either China or Japan. One of the many newly set rules in Manchukuo was prohibition of any “discussion of falling in love and lust, love triangles, denigration of women’s virginity, sex, homosexuality, suicide, incest, and adultery < …> use of matchmakers or maids as the main topics, exaggerated description of red-light districts and traditional human emotions” [2]. While male writers that tackled these topics were imprisoned or executed, the Japanese turned a blind eye on women writers “exposing reality” — this proves how little a woman’s voice meant.

However, the invaders did want to dictate their own views on Chinese women, and even if they did not give women power, they indeed tried to show them their place in society. “Educated women were advised to devote themselves to work in order to avoid degenerating into mere ‘flower vases’ to decorate the workplace” [3]. “Chinese women were urged to emulate the ability of Japanese women to “renku nailao” (bear bitterness and endure labour) [4]. The government stated that this was to avoid excessive and unnecessary sexuality and promote conservative ideals, but was it the only reason? Growing numbers of educated Chinese women also meant women understanding politics and gaining power, and new types of uprisings would not have benefited Japan in any possible way.

Rising Interest in Politics

There were, however, rapidly increasing numbers of women–beggars, starving street peddlers and concerned mothers of poor families–who decided to take part in the Communist movement, remove the Japanese out of their lands in hope of jobs and food, things they had not had for years. For instance, a cigarette peddler Yuan Hou, who had starved her whole life and faced even worse times when her village was under the Japanese rule, made a decision to become “a liaison agent for the underground revolutionary groups working in the Hsuchow area. < …> In the spring of 1944, she was accepted as a member of the Communist party” [5]. From this it is obvious that even though the Japanese did not want women getting a grasp on political affairs, they encouraged them to do so. This was a new phenomenon never seen before: the Japanese invasion was the catalyst for Chinese women to become politically active and recognised, and set the foundation for “a large-scale women’s emancipation movement, resulting in the historic liberation of Chinese women which won worldwide attention” after the Communist Party’s victory in 1949 [6].

Stories similar to Yuan Hou’s inspired thousands of Chinese women to become politically active: despite a lack of education and any political knowledge, women listened to Communist stories of a “harmonious society” and a “better world without Japanese”, which helped the Communist party gain victory. When analysing the idea of the peasantry giving rise to Communism [7], it is worth noting that there was no gender division between people getting engaged in politics. The communist party needed growing numbers, and welcomed both men and women of the peasantry to join them. On 25 July 1939, the Xinzhonghua bao (New China newspaper) published Mao Zedong’s speech at the opening ceremony of Yan’an Chinese Women’s College. His statement “The day the women throughout our nation stand up is the day when Chinese revolution succeeds, reveals that the mobilisation of women was not only part of, but also essential, for the Chinese Communist revolution” [8].

Deng Yingchao, the leader of the Women‘s Department of the CCP’s Changjiang Bureau, established in Wuhan in 1937, outlined that “the prerequisites of mobilizing women for the war effort were to improve women’s literacy and life conditions and to allow them to participate in politics. In terms of occupations, women workers could join worker unions, village women could join peasant associations, and female students could join student unions.” [9]. Even though Chinese women had become an officially recognized political force a few years before the Japanese came–by the revolution of 1926-27 (“they staged protest marches, made speeches, worked as cell secretaries, messengers, nurses, even as fighting soldiers” [10])–it was the Japanese invasion that drove the masses to join. Prior to this it was mostly the educated wives of rich and powerful men that wanted to be involved in politics (as stories in the book Echoes of Chongqing [11] demonstrate, for rich women the war was only an inconvenience disturbing women’s leisure activities), but nothing inspired poor Chinese women of the peasantry to join the Communists and fight off the invaders more than the invasion of the Japanese troops.

A Sense of Pride

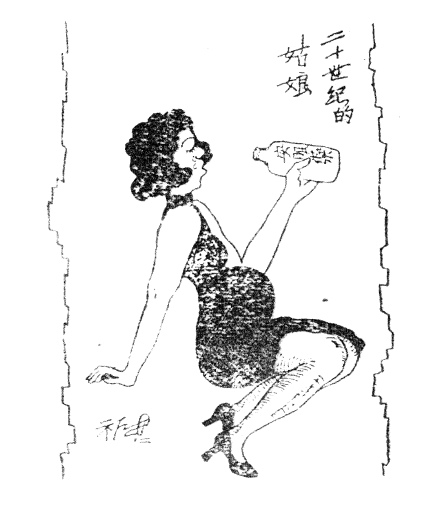

Another thing the Japanese invasion helped the Chinese women to develop was pride. The more women were mistreated, the more they felt it was wrong, and many of them decided they would rather die than humiliate themselves serving the Japanese. Even though women were always inferior to men in China, they were appreciated as mothers and family keepers, good housewives well satisfying their men. Even if one does not consider small Chinese villages or even cities such as Nanjing, where during the Japanese invasion Chinese women were raped and killed with no mercy, in places like Manchukuo women often took their own and their children’s lives to die with pride rather than live under the Japanese rule: “She spent her time washing the family’s clothes and cleaning up obsessively, nervously obsequious toward her daughter and [her husband] Dr Xia. She was a pious Buddhist and every day in her prayers asked Buddha not to reincarnate her as a woman: “Let me become a cat or a dog, but not a woman” [12]. A woman’s goal had always been to protect her family and children, and for Chinese women it was not just from starvation, but also from the immense humiliation. Japanese-sponsored Chinese-language journal Xin Manzhou (New Manchukuo) caricatured Chinese women who often assumed that a pregnant woman in Manchukuo had nothing to live for (figure 1):

Newspaper caricature of Chinese women – Manchuko women

A Chinese woman holding a bottle marked “sleeping pills” tearfully consumes the contents to end her life and that of her unborn baby. The Japanese mocked women for not realising their duty as mothers of children who had the future of the Japanese nation in their hands. But the truth was, women were too proud to be serving the Japanese for the rest of their lives, and bringing babies into that kind of world. In his book, Chang writes a story about how after a man had been arrested as an “economic criminal” for revealing he had eaten rice after he was sick and was hauled off to a Japanese camp, his wife drowned herself together with their baby. Under the attacks of the Japanese, the safest place to be was in one of the occupied territories, as it meant that it would not be bombed any more. Yet there were thousands of women moving their families to the west, further away from the invaded areas, because they would rather risk dying living a free life than live under the Japanese rule. This proves that women had developed a sense of pride over the years, and (even if using the unjustifiable measures) the Japanese made them extremely devoted to their families and the nation itself.

Towards Emancipation

The Japanese ideals seemed so intrusive that Chinese women began to have mutinous mindsets, which led to thoughts about liberation of women and feminism. “The ‘New era’ women in Manchukuo had essential responsibilities to the nation; they must not just ‘change from garbage into a toy’ – a critique of traditional and modern constructs of womanhood” [13]. By that time Chinese women had already been receiving education, but in territories occupied by Japanese, boys and girls were educated differently: “For girls the aim was to turn them into ‘gracious wives and good mothers’, as the school motto put it. They learned what the Japanese called ‘the way of a woman’ – looking after a household, cooking and sewing, the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, embroidery, drawing, and the appreciation of art. The single most important thing imparted was how to please one’s husband. This included how to dress, how to do one’s hair, how to bow, and, above all, how to obey, without question” [14].

Women were raised similarly through centuries–always to please a man–but nothing seemed more repellent than serving those of the Japanese. “In the 1930s Chinese ‘new women’ viewed Japanese constructs of ‘good wives, wise mothers’ as regressive” [15]. In her study “Women in the Chinese Enlightenment”, Wang Zheng [16] notes that “the description – or rather, the prescription – of the new woman was radically different from that of a filial daughter, good wife, and virtuous mother in the Confucian system.” The invasion gave a certain boost to feminism and eagerness to put an end to submission, to conquer the enemy not just for the freedom of the nation, but also individual independence. Many years after the war a young Chinese teacher Wang Tehying said, “Now, whenever I think of the humiliation I had to endure in those days, I hate myself for having been so weak and irresolute as to remain aloof from the anti-Japanese war then vigorously waged by the Chinese people” [17]. It was nothing else but the Japanese invasion that encouraged two famous writers Wu Ying (the author of “Yu”, Lust) and Yang Xu (“Wo de riji”, My Diary) to start a little rebellion of their own against the norms of society. They both “chose their own partners, established notable careers outside their homes, and wrote extensively about their personal beliefs and ambitions. Between the cracks and crevices of colonial enforcement, their writings gave voice to debates over Chinese ideals of sexuality and womanhood” [18]. Therefore, it can be stated that the invasion of the Japanese resulted in accelerating mind-freeing revolt against women’s inferiority and perennial submission.

Chinese Women Becoming Stronger

To conclude all of the above, besides the obvious results of the Japanese invasion, there are more than enough examples of less noticeable effects applicable just to women. Even though when one asks about the Chinese women’s position during the Japanese invasion, the first answer that comes to mind is “murder, rape and torture”, after looking deeper into the indirect effects, it is possible to see some more positive aspects. The invasion was the main drive for women to get engaged in politics in order to join the resistance movement. Since the Communist party was seeking for people to join them, they welcomed women promising them equal rights, and had numbers of party members growing rapidly. Despite some historians such as Pepper [19] who believe the Japanese were not essential to the rise of the Communist party, it is worth noting that it definitely gave it a boost, attracting many people (among which many were women) of the peasantry to join in. Not only were Chinese women not satisfied with the Japanese rule–they questioned the education and society norms brought to them by the Japanese, they spoke out against the already-designed destinies of their own and their children with national and personal pride. After the War of Resistance, this resulted in talks on liberation and ideas of feminism, and no one can say for sure when this would have happened without the Japanese invaders, if at all.

Written by: Greta Oss

Edited by: Monika Dvirnaitė

Additional information

Footnotes:

- Yang, 1941.

- Yu, 1987.

- Wei, 1943.

- Smith, 2004.

- All China Democratic Women’s Federation, 1952.

- White Papers of the Chinese Government, 1994.

- Johnson, 1963.

- Cai, Deng and Kang, 1988.

- Deng, 1988.

- Lucas, 1965.

- Li, 2010.

- Chang, 2004.

- Bai, 1941.

- Chang, 2004.

- Norman, 2004.

- Wang, 1999.

- All China Democratic Women’s Federation, 1953.

- Smith, 2004.

- Pepper, 2004.

References:

- All China Democratic Women’s Federation (1952), From Struggle to Victory. Sketches of the fighting women of New China, Peking: New China women’s Press.

- All China Democratic Women’s Federation (1953), Women of China, Peking: Foreign Languages Press.

- Bai Wu (1941), “Funii yu wenhua” (Women and culture), Daban Huawen meiri (Chinese Osaka daily), December 7.

- Cai Chang, Deng Yingchao and Kang Keqing (1988), Funü Jiefang Wenti Wenxuan 1938-1987 (Selected works on women emancipation 1938-1987), Peking: Renmin chubanshe.

- Chang Jung (2004), Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, London: Harper Collins Publishers.

- Johnson, Chalmers A. (1963), Peasant nationalism and communist power: the emergence of revolutionary China, 1937-1945, Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

- Li, Danke (2010), Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China, Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Lucas, Christopher (1965), Women of China, Hong Kong: Dragonfly Books.

- Pepper, Suzanne (2004), “The Political Odyssey of an Intellectual Construct: Peasant Nationalism and the Study of China’s Revolutionary History: A Review Essay”, The Journal of Asian Studies, 63(1): 104.

- Smith, Norman (2004) “Regulating Chinese Women’s Sexuality during the Japanese Occupation of Manchuria: Reading between the Lines of Wu Ying’s “Yu” (Lust) and Yang Xu’s Wo de riji (My Diary)”, Journal of the History of Sexuality 13(1): 57

- Wang Zheng (1999), Women in the Chinese Enlightenment: Oral and Textual Histories, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Wei Zhonglan (1943) “Xin Zhongguo niixing de dongjing” (The new Chinese women’s movement), Qingnian wenhua (Youth culture) 3: 34.

- White Papers of the Chinese Government (1994), The Situation Of Chinese Women, Beijing: Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China.

- XinManzhou (New Manchukuo) (1940), “Ershi shiji de guniang” (twentieth-century woman), no. 2, 148.

- Yang Xu (1941), “Nimen zhidao ma? Qingnian niixing de lixiang huoban shi jianchuan nuxing de xin keti” (Do you know? Women’s ideal partner is a healthy women’s new topic), Xin Manzhou (New Manchukuo) 10: 55.

- Yu Lei (1987), “Dongbei wenxue yanjiu shiliao” (Historical research materials of northeastern literature), Ziliao (Materials) 6: 181.

Photos: