One of the most famous Japanese diplomats who worked in Lithuania, Chiune Sugihara (jap. 杉原千畝, Sugihara Chiune), became a part of history as a person who saved thousands of people of Jewish origin during the uneasy times of World War II. On January 1st we were commemorating the 115 year anniversary of the birth of Sugihara and 31 year since he was announced as the Righteous among the Nations in Yad Vashem, the Israeli Holocaust Memorial. To honor Sugihara’s memory Lithuanian and Japanese artists collaborated on a joint theatre play for the very first time, it was shown in Lithuania last year.

There are probably few people in Lithuania who have not heard at least something about this Consul of Japan, who was residing in Kaunas in 1939-1940 and was helping the war refugees who fled to Lithuania, mainly those of Jewish origin, by issuing transit visas to Japan. Some years ago, Japanese journalists came to Lithuania to conduct a survey and see how well Lithuanians knew Sugihara and his work in Kaunas. The journalists went to the main streets of Kaunas and asked people what they knew about Sugihara, and were surprised that people were well familiar with him and his activities during World War II. On the other hand, there are still some misleading “truths” about Sugihara that remain present in the society. Even though there is quite a lot of literature dedicated to Chiune Sugihara, the greater part of these writings could successfully claim literary awards rather than those of fine detailed historical research. The vast amount of online writings about Sugihara in particular can be characterized as superficial presentation of facts and do not intend to seek historical truth. This article will be focusing on the issues that are usually forgotten or misinterpreted when presenting facts about Chiune Sugihara and his work in Kaunas.

Number of Jewish People Saved

The first thing that comes to the attention when analysing Chiune Sugihara’s work is the number of people he saved. Today it is impossible to determine how many Jewish people that received visas from Sugihara could have left the country together with their families. Even though the official number is 2139, a number found in Sugihara’s 32 page-long list of visas (the list is kept at the Centre for Judaic studies at Boston University), in historiography, the numbers differ from 1500 to 10 000, though the evidence is thin for the higher figure. According to Yad Vashem, which was collecting data about Sugihara from 1968, it had the information that about 6000 people saved by him.

It would be correct to say that the number of issued visas and saved people differs greatly due to one simple fact: family members could travel with one visa, because children’s names were written in their parents passports, proving that they belonged to one family and could travel with one visa. Due to very particular historical circumstances and since not everyone saved by Sugihara declared that they received help from this Japanese diplomat, it looks rather impossible to determine the exact number of people saved. Various researchers claim different numbers; however, it is noted that in order to make a bigger impression, a higher figure such as 10 000 is used, especially in the online writings about Sugihara, which are not always too reliable.

The Forgotten Consul

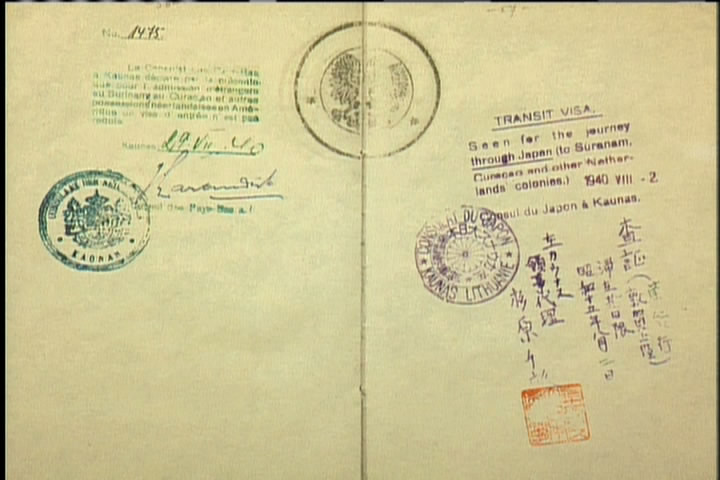

Those who are interested in Sugihara’s story, have probably heard about another foreign diplomat who was working in Kaunas at the same time as Sugihara. Jan Zwartendijk (1896-1976), a Dutch businessman, who worked for a radio manufacturer “Philips” and had nothing to do with diplomatic relations, was asked by L.P.J. De Decker, the Dutch Ambassador in Riga, to become a Dutch Consul in Kaunas after the German invasion of the Netherlands and the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in 1940. When the first war refugees reached Lithuania and started to look for ways how to escape the country they turned to the Dutch Consul for help. Zwartendijk started issuing visas to enter Curaçao, a Dutch colonial island in the Caribbean Sea. This way J. Zwartendijk created almost by accident the convenient fiction of a place of final refuge. Refugees who were not already Soviet citizens (that is, Lithuanians before late August 1940) could hope to be allowed to cross the Soviet Union to freedom. There is no record of how many stamps Zwartendijk issued, though some suggest up to 1 200 or so. He destroyed all his papers when he was forced to leave in August 1940 and return to Nazi-occupied Holland, fearful of what use either the Soviets or the Nazis might make of them – incriminating evidence of his role in saving the Jewish people. Some scholars even claim that by issuing visas, Zwartendijk was risking more than Sugihara, who had his diplomatic immunity and was safe.

Referred to as “Mr. Philips Radio”, formally it was Jan Zwartendijk who started issuing “life saving visas”, and not Chiune Sugihara. Sugihara could only issue transit visas for those who already had a visa stamp from the Dutch Consul: the Japanese government did not allow issuing visas to Japan as a destination country. Of course, Sugihara did not always follow the rules and was issuing transit visas without the visas to Curaçao. The Dutch and the Japanese Consuls are supposed never to have met, yet they became engaged in an intensive collaboration. Even though Jan Zwartendijk has also received a title of the Righteous among the Nations, this Dutch Consul receives a lot less attention than Sugihara, and is usually forgotten when talking about the Holocaust and saving the Jewish people in Lithuania.

Links with Polish Secret Service

The image of Chiune Sugihara is quite positive in Lithuania. In many articles, he is portrayed as a noble person who saved thousands of lives. Sugihara’s “legend” has made him a hero in Lithuania, a country where stories about saving the Jewish people from the Holocaust are of big importance and make Lithuanians proud.

However, the same cannot be said about Poland, where recently Polish researchers brought to light some of the details of Sugihara’s work in Kaunas that, according to them, were not so glorious and caused negative reactions from the public . Researchers focused on Sugihara’s links with Polish secret service while working in Kaunas and portrayed it in a very negative light. It seems that this has cast a shadow on Sugihara which completely eclipsed the positive merits of this Japanese diplomat who rescued several thousand people.

It is commonly believed that Sugihara was not just an ordinary diplomat residing in Kaunas. Since it was an uneasy period – the beginning of the Second World War – it is no surprise that particular countries were interested in having as much information about the flow of the events as possible, and had spies providing that information. Signing the Ribbentrop and Molotov pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in August 1939 must have been an unexpected surprise for Japan and could mean that it could no longer trust its ally Germany. Because of its good geographical location, Lithuania was a convenient place to observe and collect information about the relationship between the Soviets and the Germans and the consequences this friendship would bring.

Soon after the Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, thousands of war refugees fled to Lithuania, which at that point was still operating as an independent country. However, in June 1940, the Soviet Union took control of Lithuania, prompting many refugees to seek some means of escape.

This is where Sugihara’s links with Polish secret service comes into light. His task was to collect secret information from fleeing Polish officers about the state on the border between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. Japan needed to remain alert in case Stalin was planning a strike against Hitler, or vice versa. For this reason, Sugihara had a special group of subordinates, working at the consulate. Apart from one German, the rest of the consulate workers were agents of Polish secret service working under fake names. Studies and documents show that people who were working as Sugihara’s subordinates were undercover Polish officers, appointed to help Sugihara collect secret information. Some researchers claim that at the same time Polish secret service was also looking for ways how to save soldiers and people of Polish origin that fled to Lithuania after the Nazis invaded Poland – Sugihara was the one who could help and prepare those escape channels.

This is where Lithuanian and Polish researchers have a totally different approach towards Sugihara’s links with Polish secret service. Even though there was a great amount of Jewish of Polish origin saved by Sugihara, the fact that Sugihara was working with their secret service is condemned by Polish researchers and they present a negative image of him to the public. As for Lithuanian authors, they do not ignore Sugihara’s links with Polish secret service; however, this particular detail does not take the spotlight, and the image of this Japanese Consul remains very positive in society.

Official Reason for Dismissal from Office

It is commonly believed in Lithuania that Sugihara was issuing transit visas to Jewish people without the consent from the Japanese government and was fired because he disobeyed orders. However, there are a couple of strong arguments opposing this idea and ruining Sugihara’s image as a rebellious and courageous person, who was punished for doing a noble deed. Firstly, the Japanese government never had a negative approach towards the Jewish people and never prohibited to issue them transit visas. This was clearly stated by Yosuke Matsuoka, the Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs, in 1940 when he declared that Japan refused to support Hitler’s anti-Semitic politics. Moreover, it appears that the messages from the Japanese government to Sugihara are often misinterpreted. Sugihara was sending requests for the permission to issue visas for Japan. In their reply messages, Japanese authorities were not allowing to issue visas to those people who did not have a visa to a destination country, meaning that Sugihara could issue as many transit visas as he possibly wanted. It would have been a problem, however, if Sugihara had been issuing visas for Japan as a destination country. Therefore, Sugihara did not offend Japanese government’s policy by issuing visas for transit only.

Then why was Sugihara fired from diplomatic office? According to the official version by the Japanese government given in 1994, due to financial shortage, the country could not support such a big diplomatic body anymore and had to dismiss some of the diplomats. Another explanation was released later in 2001, saying that Sugihara’s dismissal was not a punishment, since he finished his career only in 1947, 7 years after he was issuing visas, and was granted a full pension. Moreover, if Sugihara was considered guilty in the eyes of the Japanese government, he would not have been appointed to work as a Consul in Prague, Königsberg and Bucharest after he was removed from Kaunas.

The Duplicate Stamp and the Real Reason for Dismissal?

It seems that many researchers believe that Sugihara had to finish his career because he was issuing visas without Japanese government’s approval, an idea which appears to be misleading, as already discussed before. However, only a very few authors in Lithuania suggest a different approach why this happened. As mentioned before, in historiography the number of Jewish people saved differs from 1500 to 10 000. One of Lithuanian researchers, Bernaras Ivanovas, suggests that these numbers could have been the real reason for Sugihara’s dismissal, a fact to which none of the researchers paid attention. The presumptions of B. Ivanovas are worth paying attention to and bring another point of view into the discussion.

According to B. Ivanovas, even if we believed the official version, that Sugihara was issuing visas for only a month in July and August in 1940, we would need to acknowledge that it is impossible to issue thousands of visas writing them only by hand. Eventually, the Polish secret service made Sugihara a visa stamp according to his sketch, which facilitated his work.

Even though family members could use one visa, B. Ivanovas admits that several thousand people received their visas not from Sugihara himself. This is where the researcher suggests Sugihara’s link with Polish secret service, which was making a visa stamp for him and made one more stamp for their own use. Consequently, by making the second stamp and falsifying the signature it was easy to issue visas without Sugihara. With this stamp, Polish secret service could have helped their citizens – civilians and soldiers of Polish origin – in Lithuania. The Polish secret service was trying to send some of the soldiers to France where the Polish army was formed, and the rest of them (civilian Jewish of Polish origin) were supposed to be sent as far away from the war as possible. According to the author, Sugihara was aware of the existence of the second stamp, but he did not mind that and did not do anything about it. Furthermore, the existence of the duplicate stamp could also explain the reason why there were so many people saved by these transit visas.

On the day of his departure from Kaunas, Sugihara gave away his stamp, which meant that there were already two stamps at someone’s disposal. According to Bernaras Ivanovas, this could have been the reason for Sugihara’s dismissal by the Japanese government in 1947 – Sugihara not only gave away his visa stamp, but also ignored the fact that there might have been another fake stamp somewhere used by the Polish secret service in the underground to save people of Polish origin from the Nazis. According to the author, it could have been that the principled Japanese government was shocked by the fact that by giving away the stamp to the Polish secret service, Sugihara contributed to the falsification of documents.

To sum it all up, it is likely that some of the facts about Sugihara’s dismissal will remain unknown and hidden in the archives of Japanese institutions until they are revealed, if ever. In any case, this article does not question the importance of work done by Chiune Sugihara, and is only an attempt to say that history is more complex than it might seem at first sight.

Written by: Milda Rimkutė

Edited by: Monika Dvirnaitė, Šarūnas Šalkauskas

Learn more

For further research regarding the topics discussed in both articles please refer to these sources:

- Alvydas Dargis „Japonijos konsulo misiją prieškario Kaune tebegaubia paslaptis“ [The mission of Japanese Consul in pre-war Kaunas still remains a mystery], Lietuvos Rytas, 1997, No. 70, 72, 74, 75, 77, 80, 81, 83, 86, 87, 89.

- Bernaras Ivanovas, „Chiune (Sempo) Sugiharos veiklos Kaune 1939-1940 m. probleminiai aspektai” [„Problematic aspects of the activities of Chiune (Sempo) Sugihara in Kaunas in 1939 and 1940“], Genocidasir rezistencija, 2001, No. 1 (9), p.7-14.

- Linas Venclauskas,Chiune Sugihara : Visas for Life, 2009.

- Simonas Strelcovas, „Chiune Sugihara ir Janas Zwartendijkas – Pasaulio Tautų Teisuoliai. Istorinės peripetijos tarp sovietinių struktūrų, žydų pabėgėlių ir jų gelbėtojų“ [„Chiune Sugihara and Jan Zwartendijk: the Righteous of the World Nations . Historical peripeteias among Soviet structures, Jewish refugees and their redeemers“], Genocidas ir rezistencija, 2003, No. 2 (14), p.44-50.