Looking back at the history of cinema, television and literature of the 20th century it‘s hard to miss the spread and mainstream dominance of science fiction (and fantasy) in the imagination of mankind. You‘d be hard pressed to find any person under 30 who couldn’t end the sentence “Luke, I am your …” – and the majority of these people would probably utter this phrase in the characteristic raspy voice of Darth Vader. We aren‘t even surprised by the fact that in our pockets we now carry devices that only decades ago existed only in science fiction and enable us to communicate with anyone in the world, access the breadth of human knowledge, accurately determine your location in any place of the globe and take shameless bathroom selfies. The image of Japan as the most technologically advanced society and country has established itself at the second half of the 20th century and it is no different in respect to science fiction – science fiction is widespread and mainstream in Japan and is enjoyed not only domestically, but has become one of the main export products of Japan through anime and video games. The evolution of Japanese science fiction is one of the topics that mirrors the development of Japan itself – from novelties coming from the West to a source of national pride for Japan.

Science fiction‘s journey to Japan

It‘s quite difficult to define what exactly should be considered science fiction , because the genre has a lot of common ground between other genres such as horror films and literature. You can always raise a question whether M. Shelley‘s Frankenstein should be considered as science fiction or horror? However, we can say that there are several ideas, themes and problems commonly raised by science fiction literature and cinema: 1) the invasion of forces that are outside of humanity, contacts with aliens, other worlds (or times); 2) changes in society caused by technology and science; 3) the technological modification of the body or the self (also the creation of new bodies/selves)[1].

Science fiction first emerged in Japan during the Meiji period (1868-1912); as many other things it came to Japan from the West. The Meiji period is known for the especially fierce push to modernize Japan, an almost blind faith in the power of progress, importing and adapting novelties from the West. Similarly as in the West folklore and superstitions lose their relevance and pragmatism and utilitarianism become more and more prevalent. It is no surprise, then, that science fiction, which is able to provide a glimpse at the progress of humanity, science and their consequences, established itself in Japan at this time. The work of J. Verne were one of the first to be translated and published in Japan. His Around the World in 80 Days, first published in 1873, was translated into Japanese and published in 1878. Soon after followed From the Earth to the Moon (published in Japan in 1880) and 20000 Leagues Under the Sea [2]. Time, the future, the past and continuity were one of the main concerns and topics during this period.

Science fiction was mostly popularized the same way as in the West – by various magazines that were dedicated to this topic. In 1920 a magazine called Shinseinen (eng. The New Youth) started its publication and became the mecca of tantei shosetsu (eng. detective fiction), which is now widely considered to be the precursor of modern Japanese science fiction [2]. The editor of this Magazine Koga Saburo distinguished two types of tantei shosetsu: honkaku (eng. regular) and henkaku (eng. irregular) detective fiction. The regular detective fiction features puzzles that are solved using theoretical thinking and deduction while the irregular detective fiction was addressing a different problem – times when the limits of human understanding were reached and mysterious unknown phenomena are encountered [2]. One of the best known writers of this period is Edogawa Ranpo (1894-1965), whose irregular detective fiction is considered as the start of modern science fiction and also one of its classics.

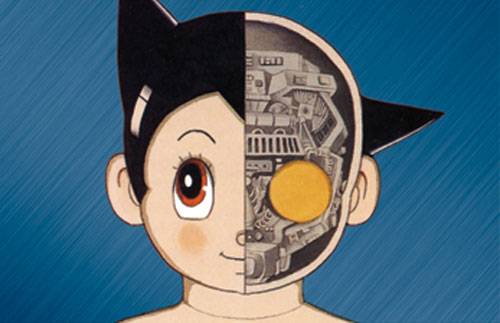

The golden age of science fiction begins with the first specialized science fiction magazines – Uchujin (Cosmic Dist, 1957) and SF Magajin (SF Magazine, 1959). This is the time when the best known Japanese science fiction authors, such as Shigeru Kayama, Kobo Abe, Sakyo Komatsu gain popularity. It must be noted that while science fiction in West developed incrementally, with one genres becoming obsolete and being changed with others, in Japan they all developed and existed at the same time – amateur science fiction, narratives about various monsters, robot rebellions and space operas coexisted peacefully [3]. At the same time the Japanese film industry is experiencing a huge boom – the cult favorite Godzilla (jp. Gojira) is released in 1954 and with it comes a huge demand for kaijū eiga (eng. monster movies). Almost at the same time legendary manga are coming out – O. Tezuka‘s Tetsuwan Atomu, M. Yokoyama‘s Tetsujin 28-gō, both of which were made into anime and shown in the USA not long after.

Tokusatsu, kaijū eiga and classical Japanese cinema

Although the products of the Japanese imagination – anime, manga, toys and cinema – are highly valued nowadays, during the period of 1950-1970 they were virtually worthless. Even the cult hit Godzilla, when it was first exported to the USA was considered to be a cheesy comedic horror film, worthy of derision rather than serious consideration or critique. Godzilla represents the then popular stylistic genre tokusatsu (eng. special effects), which can be recognized by the rubber monster costumes (suitmation acting) and small destroyable miniatures of cities. This genre is best represented in television by the super sentai type shows, such as Ultraman, Power Rangers and etc. It became popular in Japan very quickly – it was not only uniquely Japanese, it was also cheap and was able to meet the needs of the consumers in the fast rising economy. The period after the war saw a lot of American culture being imported into Japan, but the international recognition of the great film creators (such as Ichikawa Kon, Akira Kurosawa and etc.) and the tokusatsu films allowed for the Japanese to have a certain sense of pride about their production, it was a source of national pride in a country that had to completely rebuild and reinvent itself after the war.

Godzilla is a very interesting film not only because of its themes and technical aspects, but also regarding its different reception in the USA and Japan. The imagination of post-war Japan was still dominated by the atomic bomb – a force, which is unstoppable, which does not care for anyone’s feelings and leaves only rubble in its wake. The monster itself, peacefully sleeping in the underwater caves of the Pacific is woken up and genetically mutated by the H-bomb experiments being carried out by the US military at Bikini atoll. The provoked monster sinks several ships and follows its attackers to Tokyo and then almost levels it to the ground. The monster is stopped only by a fearsome weapon created by Dr. Serizawa, which was kept in secret during the war because of the destruction it would cause. After seeing Tokyo destroyed, Dr. Serizawa changes his mind, but not before making sure that he would perish in using the weapon – this way ensuring that the knowledge of the weapon is lost forever. Godzilla deals with such issues as pacifism and militarism, extremism and the destructive tendencies of mankind. During the film there is an inescapable feeling that the monster is not the “bad guy” and the military the “good guys” as is standard in Western cinema. The monster is the results of the H-bomb and the people who used it and its rage in Tokyo looks less like revenge or hate, but more like a trapped, injured and confused animal, which cannot help the destruction it causes.

From Godzilla to Gundam

Godzilla, tokusatsu and kaijū eiga films allowed for the rather niche Japanese science fiction to become entrenched as an authentic Japanese cultural product for the mass populace. This process was in essence continued by anime, starting with O. Tezuka‘s Tetsuwan Atomu (better known as Astro Boy), which is also one of the seminal works of Japanese science fiction. Tetsuwan Atomu tells the story and adventures of a boy android named Atomu. As can be expected, Atomu has many special powers – he shoots lasers, he can fly, he also has super strength and enhanced hearing as well as being able to tell if someone is lying. In deference to his superhuman powers, he appears as extremely innocent and even cute, he is also one of the first true kawaii characters. Atomu gets himself into many adventures, but contrary to expectation, these adventures are very morally ambiguous. Atomu‘s main goal is to foster peace and friendship between humans and robots when none of these parties are particularly interested in it. Despite this, Atomu also has to wrestle with the issue of his own existence – does he have that, which is called a soul, can he truly be able to tell right from wrong? These questions are raised in context of the ever modernizing Japan, which is not only recovering after the war, but does so by modernizing its industrial technologies.

Although tokusatsu films and TV shows remained popular for a very long time (the last Godzilla film was released 2004), the silver screens were mostly dominated by anime films. These films achieved a lot more attention and critical acclaim abroad. Some works simply must be mentioned, such as Uchū Senkan Yamato (eng. Space Battleship Yamato), which covers some of the same themes as Godzilla – abandoning war and militarism, the encouragement of the ideals of peace and pacifism. It can be said that the period of 1970-2000 was the golden age of Japanese science fiction; it was at this time that the best known and best recognized works were created, e.g. the works of Hayao Miyazaki Kaze no Tani no Naushika (eng. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, 1984 m.) or Tenkū no Shiro Rapyuta (eng. Laputa: Castle in the Sky, 1986 m.). Mecha – the huge robots controlled by people, usually by piloting them as vehicle – is also one of the genres of science fiction that became popular during this time. It is now synonymous with Japan itself and this is because of franchises such as Kidō Senshi Gandamu (eng. Mobile Suit Gundam, 1979 m.), Baburugamu Kuraishisu (eng. Bubblegum Crisis, 1987 m.) and Kidō Keisatsu Patoreibā (eng. Patlabor, 1988, m.) and Majingā Zetto (eng. Mazinger Z/Tranzor Z, 1972 m.).

A new wave of science fiction – cyberpunk

The period from 1980 to 2000 in Western science fiction is obsessed with one style and idea – cyberpunk. All of the silver jumpsuits and belief in the liberating power of science and progress of the previous decades is now nowhere to be seen. The world is experiencing a digital revolution, however in spite of the predictions of the previous century‘s futurologists the world remains largely the same – ruthless, dark and sometimes even more cruel because of the increased power technology exerts over our lives. Cyberpunk can be best characterized by the phrase „High tech, low life“ and has a lot of its inspirations coming from Japan. Japan at the time was already known as the land of impossible technological advances, where everything can be bought from vending machines and industry is ruled by robots not men. That is how we are able to see geisha’s in huge advertisements on skyscrapers in R. Scott‘s Blade Runner (1982) and how the main character, played by Harrison Ford, chooses to eat at a traditional Japanese roadside bar while it‘s raining. This esthetic has also become an inspiration for Japanese artists themselves; some of the best known cyberpunk films are Akira (1988) and Kōkaku Kidōtai (eng. Ghost in the Shell, 1995). Both of these films deal with the human condition in a dystopian society, although they use different premises, both of them reach eerily similar conclusions.

Akira is a film about a young biker Tetsuo living in Neo-Tokyo whose psychic powers are awakened by the military. The films namesake – Akira is a telepath of almost godly proportions whose powers are so immense that he had destroyed the original Tokyo and was locked in stasis after this incident. Tetsuo, who was always in the shadow of his friend Kaneda opposes the military and recklessly uses his powers until, finally, he succumbs to his own power – his body undergoes a grotesque transformation killing Tetsuo and Kaneda in the process. At the end of the film the out of control powers of Tetsuo are harnessed with the help of Akira and Tetsuo himself is able to overcome the limits of humanity and after fully realizing his power he becomes a big bang in a different universe.

Kōkaku Kidōtai in stark contrast to Akira is a film not about the secret powers of the biological flesh, but about the strict technological modification of the body. The world in this film is controlled by a huge electronic network which pervades all aspects of people‘s daily lives (much like the internet of our time). A large part of humanity consciously chooses to change their biological organs in favor of cybernetic brains or even whole bodies. The focus of the film is on major Motoko Kusanagi, a cyborg who is given the task of capturing a cyber hacker called the Puppeteer. There are many philosophical discussions and questions raised in the film, such as what is the essence of a human, do we lose anything when we change our frail bodies into the much more advanced cyborg bodies? In the end it is revealed that the Puppeteer is an artificial intelligence, a weapon created by the military and that has achieved consciousness, but not being able to experience mortality or reproduce could not be a true form of life. This is rectified by the Puppeteer and Kusanagi melding their consciousness in the net and giving birth to a new consciousness. The very last scenes of the film see the broken body of Kusanagi changed to that of a child and the final scene is seeing a child looking over the horizon of the city and a symbolical new beginning.

Science fiction came to Japan riding on the impulse of progress and modernization. This genre is able to perfectly articulate the unease and anxiety a society experiences because of technological changes, progress and the loss of tradition and continuity. It finds a home in the Japanese imagination and after the Second World War it becomes not only a source of national pride, but also one of its core export products. Little by little the ever more popular genre finds niches in literature, film and animation, such as mecha. The unique historical and cultural experience of Japan is clearly felt in these cultural products that stimulates the imaginations of people all over the world.

Additional information

- Telotte, J.P. (2004) Science Fiction Film, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Matthew, R. (1989) Japanese Science Fiction. A View of Changing Society. Nissan Institute of Japanese Studies: Oxford.

- Bolton, C., Csicsery-Ronay Jr., I., Tatsumi, T. eds. (2007) Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams. Japanese Science Fiction from Origins to Anime, University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis.

- Napier, S. J. (2005) Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle, Palgrave Macmillan: New York.